- Home

- Marc Santailler

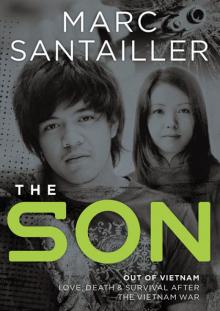

The Son

The Son Read online

PUBLISHER: Hunter Publications

EMAIL: [email protected]

WEBSITE: www.marcsantailler.com

This is a work of fiction. Aside from the historical context, all characters and events are imaginary, and any resemblance to real people, alive or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright ©Marc Santailler 2013

First published in Print and as an eBook in November 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded or otherwise), without prior written permission of the copyright owner.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA

CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

AUTHOR Santailler, Marc

TITLE The Son: Out of Vietnam Love, death and survival after the Vietnam war / Marc Santailler

ISBN 9780992330316 (ePub, Mobi)

SUBJECTS Fiction - Thriller

Fiction - War

Fiction - History

DEWEY NO A823.4

DESIGN Reno Design | www.renodesign.com.au | R33015 Graham Rendoth | Ingrid Urh

Digital edition distributed by

Port Campbell Press

www.portcampbellpress.com.au

Conversion by Winking Billy

TO THOSE WHO DIDN’T MAKE IT

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE: HARPER’S END

PART I: HAO’S STORY 1

PART II: NASTY BUSINESS

PART III: THE AGENCY

PART IV: HAO’S STORY 2

PART V: MEN WITH GUNS

PART VI: PICKING UP THE PIECES

EPILOGUE: NEW BEGINNINGS

PROLOGUE

HARPER’S END

Between Sadec and Mytho, as you head back towards Saigon (or Ho Chi Minh City as it’s now called), along Highway 1 in the Mekong delta region of southern Vietnam, lies the Plain of Reeds. This is a desolate, inhospitable stretch of country which juts down from the Cambodian border in the shape of an inverted triangle, and the road cuts across its lower extremity for about forty kilometres. Long used as a refuge by bandits and rebels of all kinds, during the Vietnam War it was a stronghold of the southern communist guerrillas known as the Viet Cong.

Harper drove carefully, his eyes straining in the weak headlights of his rented car to detect the worst potholes before his front wheels actually hit them. The road was too rough to allow for much speed, and in any case the advice at the last check point had been very clear: drive slowly, no more than thirty kilometres an hour, with your ceiling light on. That’s the signal that you’re local traffic, and they’re more likely to let you through. As an extra precaution Harper had swapped his cigarette lighter for a greasy cap, tucked his fair hair as much as possible under it, turned his shirt collar up. You couldn’t rely on the Viet Cong being colour blind.

A rough-looking lot these local government militia, barely distinguishable from the VC in their black pyjamas, guarding a bridge and a minuscule hamlet through the hours of darkness. They probably had some deal going with the VC, and it was a toss-up which was more dangerous: to stay there the night or take his chances on the road. But they knew the area, and they’d calculated the risks. By daylight the road was safe enough. It was only at night that the Viet Cong came out to assert their control, and until about eight or eight thirty you had a good chance of getting through. After that the risk of being shot at increased with each passing hour. After ten you had to be suicidal to try it. It was now twenty to eight.

A torch waved him down ahead, a string of armed men along the road. VC or good guys? Harper’s heart beat faster, until he saw the GI-style helmets. An army patrol, six or seven slim figures in khaki, led a diminutive sergeant. Harper slowed to a stop.

‘Why you on this road?’ the sergeant asked in halting English, pistol on hip, his head in its tin pot huge on his wiry body. ‘Too much danger.’

‘I’ve had a breakdown,’ Harper answered in Vietnamese. ‘Xe tôi bị hư’, phải xửa, mất nhiều thì giờ.’ The sergeant stared. How do you say radiator hose in Vietnamese? ‘I have to be back in Saigon tonight.’ In the background, occasional thumps in the darkness, grenades or mortar rounds, a flare or two and the rattle of small arms. A local firefight, or someone just showing he’s awake?

‘Dangerous!’ the sergeant repeated. ‘You shouldn’t be out so late.’

‘How’s the road ahead?’

‘Alright so far. Don’t waste time. You’ve still got twenty K before you’re clear.’

‘OK, thanks.’ Harper passed over his remaining cigarettes. The sergeant grinned briefly.

‘Good luck.’

Harper drove on, thinking of the girl waiting for him in Saigon. Hien, looking like a school-girl in her white áo dài. She couldn’t stay beyond eleven, her parents would have a fit if she stayed the night. Even if they were virtually engaged. Like all young men facing marriage, Harper still had twinges of doubt. How would it work out, taking an Asian bride of nineteen back to his family in Australia? How would she face up to the demands of the job, the moves, the constant shunting from pillar to post? She’d fared well enough with his colleagues in the embassy, her English was good and improving fast, she had brains as well as beauty: this was no shop-worn bar-girl, everyone could see that at a glance, but a girl of good character from a well-known family, and she had the strength and the toughness to adapt.

And how would he fare, as a faithful loving husband? Think of the girls you’re leaving behind. He did a quick review of the more recent ones. No regrets there. You couldn’t live like a playboy forever. She was the nearest to permanent bliss he would ever find.

What was it she wanted to tell him, that she’d refused to say on the phone?

‘Guess!’ she had said that morning. ‘If you guess right we can do it again tonight.’

Harper had a vision of her face, her impish face split by a grin of glee as she wriggled naked on top of him, biting his nose, her rump sliding like silk under his hands. ‘Yes,’ he had said, and ‘Yes,’ he said again, ‘you and me together, we’ll make it work.’

Another waving torch, another patrol. Same routine. Danger, what are you doing here at this hour? More thumps and flashes in the night. Some poor bastard must be copping it. Harper was relaxed, unafraid. Perhaps he should have waited until the next day, but how could he foresee the burst hose, the stops to fix it with wire and sweat rag until by sheer luck he’d found a good mechanic at the last place? Luckily it now seemed to be holding, and what was the point of living if you couldn’t take a risk from time to time? There’d be time enough for caution when he was old and spent and had only memories to live on.

‘About five clicks. Chừng nӑm cây.’

Ten more minutes. Two, three kilometres ahead, the lights of another hamlet glimmered through the trees, Thiên Lương, the end of the bad stretch. After that, the main road from My Tho to Saigon, total safety, an hour and a bit to get home and hold Hien in his arms.

The tracer bullets cutting across the road twenty metres ahead of the car registered in his mind before he heard the sound of fire from the trees. AK-47, he thought automatically. Shit! Favourite weapon of the Viet Cong. Stop or crash through? Keep going, that was the only hope. He tightened his grip on the wheel, slid down into the seat, put his foot down hard. Keep grinning Hien. I’ll be home tonight.

The next burst caught the car side on. Harper heard the hammer blows against the body, the burst tyre, fought to hold the wheel as the car slewed across the road. The shattered window, the splash of light in his shattered brain were the last things he knew as the car plunged over the embankment and into darkness.

PART I

HAO’S STORY 1

CHAPTER

ONE

My name is Paul Quinn. I’m Australian.

Many years ago, when I was a young man and considered by some capable of almost anything (except treason), I was recruited into a secretive government organization in Canberra that used diplomatic cover. My first posting was Saigon, near the end of the Vietnam War. It didn’t last long. The war ended sooner than anyone expected, and we all had to leave in a hurry. But during that time two things happened which were to change my life later on, and the lives of several other people.

First, soon after my arrival, I met a girl at a party. A Vietnamese girl, or young woman. The party was at the house of my predecessor, another young man, named David Harper. He worked in the political section of the embassy, where among other things he was in charge of press affairs – always a useful cover for an intelligence officer – while I did some language training in-country before taking over from him at the end of his tour. In those days the organization was still small and junior officers were often sent out on their own.

The girl was very attractive, with that mix of willowy grace, strength and intelligence which I found so captivating in Vietnamese women, and I would have liked to know her better. But she was there with her fiancé, a gangling young man from the Faculty of Sciences, and I didn’t insist. There were lots of attractive girls in Saigon. I soon had other things to worry about.

Two weeks later David was killed. He had gone down to Can Thơ, a large town on the Mekong, to meet a new contact with links to the Viet Cong leadership, and on the way back his car was shot up by – it was presumed – a Viet Cong sniper. Naturally I was pulled off my course at once to replace him. My first duty after informing headquarters was to go down to the delta to bring his body back to Saigon. Put some iron in your soul, my ambassador said, and teach you not to do anything so stupid.

The embassy was in shock. Diplomats’ lives were not without risk, but they rarely ended so brutally. Nobody could work out why Harper was on that road after dark. There was no need for him to rush back to Saigon that night, and he’d been around long enough not to take risks like that.

David had died in late February. In mid-March the North Vietnamese launched their last offensive of the war, in the Central Highlands. Six weeks later, after a series of lightning successes on their part and dismal failures by the South Vietnamese, they were on the outskirts of Saigon, massing for the final assault. The embassy withdrew in stages, the last wave leaving on the twenty-fifth of April, Anzac Day, 1975, five days before the final surrender.

Fifteen years of war had killed 58,000 Americans, 500 Australians, and probably millions of Vietnamese of both sides – and now it was over. An uneasy peace fell on the south, as the communists imposed their harsh and unforgiving rule. The era of the boat people was about to begin.

By then I’d forgotten all about that girl, and our brief meeting.

She remembered.

Twenty years later, in early 1995, many things had changed in my life. I had left government service to try my luck in business, and I lived in Sydney, where I ran a small personnel agency. I was forty-five, divorced, and I lived alone.

One afternoon in the late Australian summer of that year a Mrs Hao Tran phoned me at work. I’d never heard of her, but she was the girl I had met long ago at that party of David’s in Saigon. Tran was her married name. She lived in England now, she said, and she was in Australia on a visit. She asked if she could come to see me, as she needed my advice about a problem she had.

When I asked what kind of problem, she said it was personal, complicated, and had something to do with David. She was quick to add that they’d never been close, and yet the problem related to him. When I pressed she pleaded.

‘Please, Mr Quinn. Apart from you I don’t know anyone in Australia who might be able to help me. You were his friend–’

She told me she was staying in Marrickville, about forty minutes by train from our office in North Sydney, and I agreed to see her that afternoon, as soon as she could make it. It was a Friday, just after four, with work about finished for the day. We were on the sixth floor of an old office block, not far from the station.

‘Thank you very much, Mr Quinn. You don’t know how much I appreciate this.’

She sounded as if she meant it. I wondered what I was letting myself in for.

CHAPTER TWO

Mrs Tran was a slender, very pretty woman in a dark two-piece suit, somewhere I thought in her mid to late thirties. I didn’t recognise her of course. Twenty years is a long time. But I was struck by how attractive she was. I was used to seeing pretty women in my office – we dealt mainly with secretarial applicants – but she was a honey.

She was tall for a Vietnamese, almost as tall as me in her heels, with the long legs of a swimmer or a ballet dancer, and she had beautiful eyes, dark and intelligent in a pale oval face of almost classic perfection, the Asian cheekbones not too pronounced. Long black hair pulled back and gathered at the back of her head, light make-up, almost no jewellery. When we shook hands I smelt the delicate scent of jasmine. I also noted dark shadows under those eyes, an air of strain and tiredness. Her problem must be keeping her awake at night.

We sat in my office. Vivien Berridge, my assistant, offered us some mint tea, and while waiting for it I asked my visitor some questions. She said she lived in Leeds, where she and her husband had settled after being accepted in Britain as refugees in 1980. This was her first visit to Australia. In Marrickville she was staying with relatives, cousins of her husband, who owned a small Asian supermarket there. (Marrickville, I knew, was a suburb near the airport, which housed part of Sydney’s Vietnamese community.) She had been there over a month.

‘Is your husband with you?’ I asked.

‘No. I’m a widow, Mr Quinn. He died over a year ago.’

She spoke excellent English, with just a trace of an accent: more a question of rhythm, a way of detaching her words which gave them a faint metallic edge.

‘In fact that’s one reason why I’m here.’

Vivien brought the tea, and left soon after, having stayed long enough to get a good look at my visitor. She was a kind, grandmotherly woman of sixty-two who had herself lost her husband some years earlier, and we got on well together. I foresaw questions on the Monday morning.

Meanwhile I went on with my own questioning.

‘I don’t expect you to remember me,’ Mrs Tran said. ‘There were lots of people at that party. I was there with my sister.’ I could recall the party, more or less, but of a sister I had no memory. Yet something tugged at my mind. ‘I remembered you because you spoke such good Vietnamese.’

I couldn’t help smiling. ‘You spee Yetnamee so goo,’ the girls used to croon in the bars of Saigon, in rank exaggeration. I’d already done three months of Vietnamese before leaving Australia, but it takes much longer to master the language.

‘You wouldn’t say that now,’ I said. ‘I doubt I could string two words together any more. Mrs Tran, I’m curious. How did you find me? Here in Sydney?’

‘I rang your former department in Canberra.’

‘Foreign Affairs and Trade?’ I said, naming the Commonwealth department that gave cover to my old employer.

‘Yes. Your Foreign Office. I thought you might still be working there. But someone told me you were here.’

‘I’m surprised they remembered me. It’s more than ten years since I left. Who did you speak to?’

‘A Mr Bendix, I think,’ she said. ‘He asked to be remembered to you.’

‘Roger Bentinck. I know him. He’s an old friend.’

That explained it. Bentinck was another of my former contemporaries in the organization, who had stayed on and was now a senior officer there. Someone in the Department must have put two and two together and switched the call through to his office. We still kept in touch, although I hadn’t seen him for over a year.

Time to get down to business. She sat upright in her chair, patiently putting up with my questioning, like an applicant be

ing interviewed. From the start we’d been formal with names, but there was a deeper reserve about her, almost a wariness. Her handshake had been cool and firm but quickly withdrawn. Perhaps this was just a standard defence for such an attractive woman. When I drank my tea the scent of jasmine lingered on my hand.

‘So,’ I said. ‘You have a problem. Something to do with David. Don’t worry. I’ll be happy to help if I can.’

‘Thank you.’ She took a deep breath. ‘It’s about my son. My adopted son, rather. Eric. He’s here in Australia, and I’m afraid he’s getting into trouble.’

‘What kind of trouble?’

‘I think he’s fallen into dangerous company. I’ll explain. It’s a bit complicated. He’s actually my nephew. His mother was my sister, and his father was David.’

‘I didn’t know David had a son.’

‘David never knew him.’

CHAPTER THREE

When David Harper met Hien, in late 1974, she was eighteen, the younger of the two sisters. Their father, Hoang van Lam, owned a newspaper in Saigon, and was a deputy in the National Assembly, a member of the opposition. David used to visit him at home from time to time to discuss politics. It was a case of love at first sight. She was pretty, intelligent, vivacious, he was handsome, single, spoke fluent Vietnamese. Their parents tried to warn her against mixing too freely with a young foreigner, but she was an independent girl and soon they were seeing a lot of each other. By the end of that year they’d decided to get married, at the end of David’s posting, due in mid-1975.

‘You may remember her, Mr Quinn. She was working in the embassy by then, in the Aid section. David helped her get the job.’

‘Vaguely. I wasn’t in the embassy very long. She worked in another building.’ I had a faint picture now, of a strikingly pretty girl in a white traditional áo dài.

The Son

The Son