- Home

- Marc Santailler

The Son Page 15

The Son Read online

Page 15

In 1960 Loc had come south again. He was married by then, with one child, but his wife and child stayed in the north. He’d fought in the south until 1966, when he had been badly wounded in a B-52 strike. He had been evacuated secretly out through Cambodia and back to the north, where he recovered.

There was a gap of a few years, but it seemed he’d returned south in 1972, and stayed there until the end of the war. By then he was a senior cadre with the Viet Cong. He’d had another child by then, a boy. But during the American bombings of the north his wife and both his children had been killed. He also had a younger sister, who’d stayed south after 1954 and joined the Viet Cong. She’d been captured by the South Vietnamese, under the Phoenix programme, which tried to turn captured Viet Cong and run them back against their own people. She’d refused to cooperate and they’d tortured her to death.

After the communist victory in 1975, Loc, who was then very senior in the party, had become deputy chairman of the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Committee – a kind of deputy mayor, as Quang had said. That was when Quang had first met him. Roger talked a bit about Quang, without revealing that he knew Quang personally. He stressed that Quang was not a communist, never had been, didn’t like them very much, but had deliberately stayed behind rather than flee abroad, to help his country through a difficult transition. He had been a high official under the previous government, and because of that had had to go into re-education.

Loc himself didn’t approve of re-education, he thought it was unnecessarily harsh and wasteful. He’d heard about Quang and arranged to have him released and attached to his staff. They had become friends, and Quang had helped him a lot in running Ho Chi Minh City. Later, Loc had seen that things weren’t working out well for Quang, and had helped Quang leave Vietnam. He himself had stayed. He was a communist, Vietnam was his country, he wasn’t going to leave it just because things weren’t working out quite as he had hoped. He had fallen from grace for a time, lost his job as deputy mayor, but later had come back into favour when the conservatives became less powerful in the party, and he had gradually moved up until he was now Deputy Premier for the whole country.

‘Here is a man who lost his father to the French, and his brother, whose family was killed by American bombs, who lost his sister in a very nasty way to the old South Vietnamese government – and yet he has no feelings of revenge. He’s never wanted revenge. He wants Vietnam and the US to be friends.’

‘That’s the man they’re planning to kill. The top liberal among the communists in Vietnam. One of the few people there who understands the west, and wants to open up his country and maybe liberalise it a little.’

‘So you’d have to ask yourself. Is that the right way to get revenge on Vietnam, and punish the communists for what they did in the past?’

Roger paused. Eric had sat riveted throughout, even the rest of us, who knew more about the subject, were impressed.

‘You see what I’m getting at, don’t you Eric. And why I think you’ve done the right thing in coming here to talk to us. We need your help, Eric. You’re probably the only person who can stop this mad scheme, to kill the one man who’s in a position to do something good for Vietnam.’

‘Now it’s your turn, Eric. Paul has told us a lot of good things about you. So we’ve decided to trust you. But now we need you to trust us. So I’d like you to tell us what you know about this group. How you came to join them, and what you’ve been doing up to now. Tell us what you’ve told Paul.’

This was the tricky part. But by then Eric was completely in their thrall, and he told them everything he had told me over the past two weeks, willingly or otherwise. By the time he’d finished they knew as much about the Mad Buffaloes and their leaders as Eric was ever going to be able to tell them, and more than I’d found out.

‘Tell us about that last session up in the hills.’

Again more detail. Besides the .303 rifle they’d fired an M16, the standard American infantry rifle in Vietnam, and also a couple of pistols: a North Vietnamese Tukarov and a .38 Smith and Wesson revolver, which they’d learnt to strip and reassemble. But most interesting was another weapon, which only Eric had been allowed to fire: a .22 pistol, a Walther PPK apparently, with a silencer. That was a professional assassin’s weapon, and Eric had become proficient with it.

‘OK.’ Roger called a halt. It was now twelve thirty. ‘There are still a few things to discuss, but let’s break off for lunch. Are you still with us, Eric?’

‘Yes, most definitely.’

‘Good. I need to take Paul away for a bit, but we’ve arranged for Sam to take you to lunch and show you something of Canberra. You haven’t been here before, have you?’

‘No sir.’

‘You can call me Roger. We all use first names in the Agency. We’ll all meet back here after lunch. Keith has something else on but he’ll be back then too. Does that suit you?’

‘Yes. Thank you very much.’

I bet it does, I thought as he cast a quick glance at Samantha, who gave him her slightly wicked smile.

‘He’s really very good,’ Roger said in the car. ‘I hope we’re not asking too much of him.’

‘I hope so too! You were going at it a bit strong there for a while.’

‘I wanted to make sure we had him on side. We can’t afford any backsliding.’

‘I’m sure there won’t be any.’

Roger wanted to go to Parliament House. I took Northbourne Avenue and began the long drive south towards the lake.

‘Get any more details about the visit?’ I asked.

‘We’ve got some dates now. He’s arriving on the second.’ The second of May. Just over two weeks away. ‘That’s a Tuesday. Coming first to Canberra, just transiting Sydney on the way in. One night here, back to Sydney the next day, one night there and then out again. Here he’ll be having meetings with the Deputy Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister, a courtesy call on the PM, and addressing a lunch at the National Press Club.’

‘Bringing many people with him?’

‘Only a couple of aides. He’s travelling light. Someone from their Ministry of Foreign Trade. I think he mainly wants to talk aid. And a security guy, some senior minder from their Ministry of Public Security.’

I drove through Civic, the old Canberra city centre, then followed Commonwealth Avenue over the lake and up the long slope to the new Parliament House. I parked in the underground car park and we took the lift to the top of the building and the grassy slope which overlooks the main entrance, stopping on the way for sandwiches and drinks at the cafeteria. We stood for a while looking at the view. We were facing north, back over the lake, towards the War Memorial away on the other side, with the wooded hump of Mount Ainslie at its back. Down the slope in front of us the old Parliament House stood like an old-fashioned wedding cake. Beyond, more official buildings, open spaces, further away residential suburbs, and on the far right faded khaki hills on the horizon, beyond Canberra Airport. It looked very peaceful, an unlikely setting for murder.

‘He’ll be staying at the Hotel Canberra, just down the road.’ Roger pointed the way we had come. ‘We’re picking up the tab. From there he’ll be coming straight here for his official calls. Driving up the road here, dismounting in front of the main entrance. Dinner that night in one of the smaller dining rooms. Only a small gathering, hosted by the Deputy PM, with a few MPs interested in trade with Vietnam. Their ambassador of course. No wives. Driven back to his hotel. Next day, lunch at the National Press Club. Then straight to the airport. He’ll no doubt be spending the morning with their embassy, but we’ll be providing escorts to and fro.’

‘What about demonstrators? Aren’t they coming in buses from Sydney?’

‘They’ll be kept well away.’ He pointed to a roadway that cut across our front, some distance down from the main entrance. ‘There’ll be barriers along that road, and they’ll remain on the other side. There’ll be lots of police about, both here and at the hotel. I don’t see anyone

taking a pot-shot at him here, do you?’

I looked down at the scene.

‘You think they’re more likely to try it in Sydney?’

‘That’s my guess. The trouble is we don’t have all his programme there yet. He’ll be meeting the Premier and some business leaders, trying to get them interested in investing in Vietnam, and there’s another meeting organised with local Vietnamese businessmen. All closely monitored, only people with a clean slate. Interestingly, your Mr Bach is among them. He really seems to be playing both sides of the street! And New South Wales police will provide protection of course. But that’s all we have, no timings or anything else yet. We don’t even know where he’s staying.’

‘Does he know about all this? Are you going to try and warn him?’

‘We’ll probably do it through the Foreign Minister. They’re having a separate session, behind closed doors, we’re hoping to get Bill in there for a private chat.’

‘Why don’t you do it through his embassy?’

He hesitated. ‘We think it’s better if we tell him direct. Otherwise they might use it for propaganda, against the Vietnamese community here. I’m told he speaks passable English, but we’ll have our own interpreter there too.’

‘You’ll have a job getting him away from his minders.’ There was something funny about that arrangement, but I didn’t seize upon it there and then.

‘What about Bach?’ I asked. ‘Found out anything about him yet?’

‘We’re starting to get a few details. We found out how he got here. From Immigration, as you suggested.’

‘And?’ I prompted. He seemed reluctant to give out trade secrets, even to an old hand like me.

‘He came out through Pulau Bidong, in Malaysia, that’s where he was processed.’

‘Did you manage to get hold of Svensson?’

‘We did. But he doesn’t know anything. He remembers the boat, more or less, but for some reason he wasn’t involved in those interviews.’

‘Who did him then? The Americans?’

Again that hesitation.

‘Come on! I did that job too, remember? I know the drill.’

‘We’re still waiting for traces from them.’ And then he closed up. Once again I had that uneasy feeling.

‘What are you planning for this afternoon?’ I asked. ‘More of the same?’

He grinned.

‘No. We’ve covered all that. Now it’s just a question of detail. Meeting arrangements and so on. It shouldn’t take long. You don’t have to be there, if you want to take time off.’

‘No, I want to be there. You’re going to be discussing contact arrangements, that involves me too.’

‘Not any more. We want to set up our own direct arrangements with him.’

‘How are you going to do that? Through his aunt? She may not want to talk to you. I had enough trouble persuading her that it’s OK so far.’

‘We don’t want to involve her either. We’ve worked something out, you’ll see. It’s much safer that way.’

‘I don’t want him put in any danger, Roger!’ I said sharply.

‘Rest assured, neither do we.’

‘How long do you plan to use him?’

‘Just a few days. All we want is information. That’s all. It’s all well and good knowing they’re planning to kill Loc, but until we know how the information’s not much use.’

‘And when you’ve found that out? What happens then?’

Again he hesitated.

‘It depends on what he tells us. Look, stop worrying! We’re being very careful here, Paul. He’s in more danger associating with you than anything else right now. We’re moving up to Sydney tomorrow. Setting up an operational base there, with Samantha on standby, ready to meet him whenever he calls a meeting. And we’ve started talking to ASIO. In fact we need to set up a meeting with you there. They want to talk to you. And we’re also talking to the police. Don’t worry, we’re making sure he’s protected, we’re not going to let him get hurt.’

‘I hope not!’

‘Now if you have no further questions we’d better get back.’

He turned away but I stopped him.

‘Wait. There’s one more thing. The price has gone up.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Passports.’

‘Passports?’

‘Yes. I want two Australian passports. One for Eric, and one for his aunt if she wants one. Not straightaway, but when this is over.’

‘Paul! Have you gone crazy? That wasn’t part of the deal.’

‘It is now. Look! I brought him to you, in good faith, so you could make use of the information he’s got, and judge for yourselves how much trust you can put in him. And yes, so you could use him a little longer if need be. But this is getting a bit more ambitious, Roger, and I’m starting to have doubts about it. So this is the deal! Either you arrange for him to get a passport when this is all over, or I pull out. And I pull him out with me. And don’t forget his aunt!’

What she’d say to that I could only guess. But I’d face that later.

‘Come on Paul,’ Roger pleaded. ‘You know we can’t do that! The Minister will have a fit if we ask him! Christ, it’s hard enough to get a passport under alias, we can’t give these things out to just anyone–’

‘Not just anyone, Roger!’ I said hotly. ‘This is a kid whose father was Australian, who got himself killed in the line of duty, a kid who himself would have been born Australian if our government in 1975 hadn’t been so shitty over Vietnam! His mother died trying to bring him out here! Do you want me to tell him how Canberra refused to accept her? That’ll put a dent in his motivation! So either you go to your minister and get approval, or we both pull out and you can kiss your operation goodbye. We’ll go to the cops in Sydney and they can take it from there.’

Roger listened in silence, his face set.

‘OK. I’ll see what I can do,’ he said after a while. ‘But I can’t promise anything. Not about her. Why don’t you just marry her for God’s sake!’

‘Leave my private life out of this!’ I snapped. He stared at me.

‘Christ, she really has got under your skin! OK. I’ll see what I can do.’

‘I want your word!’

‘Yes! I promise! Satisfied? Bill will simply go berserk.’

Bill can go fuck himself, I thought. But at least I’d won that point. What good it would do was for me to work on.

The afternoon session went much faster. Roger left as soon as we got back to the house, to confer with Bill Forsythe no doubt, while Keith and Samantha went over the details of contact arrangements in Sydney with Eric. They were simple, and just shady enough to pass as genuine. Samantha was to be Eric’s girl friend–

‘But I already have a girl friend,’ he said.

‘All the better. That way you’ve got more reason to keep Samantha secret. She’ll use her real name, but she’s from Sydney, here’s her phone number, you met at Bondi and you’ve both got the hots for each other. So when you feel the need you just give her a ring, and come out to meet her. You can meet in town over coffee, or go for a walk somewhere quiet. Be prepared, she’ll change her appearance a little. And you just tell her what you know. She’ll give you instructions. OK with that? Don’t worry, you won’t be called on for any scenes of passion. Just hold hands as you huddle over a drink or walk along the beach.’

He smiled at the thought, and there was amusement in her eyes too as she contemplated having assignations with this tough-looking kid with the smouldering eyes. She had taken him up to Black Mountain tower for lunch and they seemed to have become very chummy all of a sudden.

Roger came back as they were finishing up. He had a quick word with me first, his manner terse and not very friendly.

‘I talked to Bill. He’s not happy, but I put your arguments to him and he agreed to do what he could. We’ll put it to the Minister. But not until this is over. Then we’ll have a good case, and he’ll probably wear it. Sorry,

that’s the best we can do.’

‘I understand. Thanks. But I’ll hold you to it.’

‘I’m sure you will.’

Then he went back to Eric, all avuncular once more.

‘Got everything worked out? Are you happy with it, Eric?’

Eric was happy. His eyes were dancing with excitement.

‘Good. It’s not too late to back out you know. What you’re doing takes courage. I can see you’ve got that, you’re a lot like your father, and from what I’ve been told your mother was very courageous too. So you’re doing them proud. But it’s not too late to pull out. No one here will blame you if you do.’

‘No. I want to get on with this.’

‘We’re going to back you all the way. We’ll have people on the ground to make sure nothing goes wrong. And we’ll sort everything out with the police in Sydney. So you don’t have to worry about that. But you’ll be on your own for much of that time. Think you can handle that?’

‘Yes.’

‘I think so too. But remember. We don’t want you to take any risks. Once you’ve found out what they’re planning, get in touch with Sam. Don’t lose her number. OK? You can still keep in touch with your aunt, of course you can, but you mustn’t go anywhere near Paul. Not until this is over. It’s too risky for you. Paul understands that too. He’ll drive you back to Sydney but after that you don’t have any further contact until I tell you. All agreed?’

‘Yes. Perfectly.’

‘Just one more thing.’

Like a magician Roger produced a large manila envelope from his briefcase, from which he pulled out his rabbit of the day.

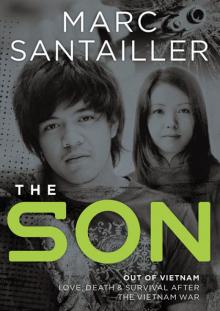

‘Paul told us you didn’t have any photos of your father. These are for you.’

They’d done a good job, and the two large glossies would have done a portrait photographer proud: two full-face shots of David, taken at different times – one on his first entry into the firm, the second some time later, probably when he set out for Vietnam – making him look young and fresh and eager, like a student on graduation day. And a third smaller print, even more telling, taken at the training establishment, David doing unarmed combat, with the instructor’s face carefully blacked out. Eric studied them in silence then looked up, almost too moved to say thanks.

The Son

The Son